When I talk to patients about fat transfer, they will often say to me somethign like:

"I have a friend (who maybe has a friend) who got fat transfer and she says that it didn't last and it all just disappeared".

Right. Let's talk about this. It is clear that there are enough patients who have had bad experiences with fat transfer that this sort of comment is made a lot when I discuss fat transfer. And it is also (unfortunately) clear that there are surgeons out there who, perhaps for commercial reasons, have decided that shitting on fat transfer is good for their business. On top of that, there seem to be a bunch of so-called influencers who've taken it on themselves to throw a bit of shade at the technique (experts, no doubt, that they are).

So I'd like to offer you my thoughts. Clearly, as someone who does it, thinks it works, and has the experience to show it works, I am coming at this from the perspective of what I would call reserved optimism.

I have said many times before that fat transfer isn't perfect. It isn't a technique for everyone, and it has limitations.

But that doesn't mean it doesn't work. It just means you need to be educated about what you're getting into.

First: fat transfer is permanent...if it is done properly.

The basic concept of fat transfer is that fat is taken from one place in the body, moved to the breast, where it then develops a new blood supply, and once that blood supply has grown and can nourish the fat cells, the fat becomes a permanent element of the breast. Once those cells have a new blood supply, they cannot just die.

What that tells us is that the permanence of the fat transfer is therefore dependent on the fat cells surviving until the blood supply has grown.

So how does that work? Let's zoom in a bit for a second.

When fat has just been injected into the breast, there is no blood supply keeping the graft alive. But, the cells can still be nourished by the process of diffusion. Fundamentally, we're talking about there being some degree of nutrient and oxygen movement into the fat cells from the surrounding tissues, through a fluid medium. This process has very clear (and quite well defined) limits. Diffusion can only occur across very small distances.

That distance has been experimentally confirmed to be about 1mm at most. So, if the fat injection leaves behind very tiny, very narrow "ribbons" of fat which are no more than 1-2mm in diameter, then the oxygen and nutrients can diffuse from the surrounding tissue, into the injected fat, and importantly across that small distance can adequately nourish the fat right across the width of that narrow ribbon of fat cells. Over the next 72 hours, a process of new blood vessel growth then takes place, with an associated inflammatory response.

What this then tells us is that if the fat is injected in big clumps which are thicker than 2mm, the limits of oxygen diffusion into that clump means that only the outer 1mm will be oxygenated but the central core of the clump will not be. That central area of fat will then DIE. This is fat necrosis.

So, very clearly, the technique of injection will determine the success or otherwise of the fat transfer. If fat is injected carefully, so that many tiny little ribbons of fat are laid down throughout the breast, each of which being separated from the next by healthy breast tissue (from which a new blood supply can grow), then the fat will survive to a significant extent.

On the other hand, if the fat is injected carelessly, under high pressure, resulting in large accumulations of fat within the breast tissue, then we are going to see large areas of fat necrosis (which then end up forming hard, painful scars or potentially oil cysts if the fat cells break down completely and liquify). Which is very bad, by the way.

Closely linked to injection technique is the concept of volume limits to fat transfer. The basic idea is this: the size of the breast you are injecting with fat determines how much fat can be injected. So if you start off with a very small breast, then only a small amount can be added, whereas a larger breast will allow a larger volume to be injected. We can consider an analogy of two sponges - one small and one large. If we consider the injected volume of fat into a breast to then be represented by the amount of water that can be absorbed by a sponge, then we start to get somewhere.

The limit though isn't just about having enough "space" in the breast to fill up with fat. What it also involves is the idea of tissue pressure, because the breast is, by definition, what we can consider to be a closed space. The breast tissue is surrounded by a layer of fascia, which doesn't easily expand. This then reinforces the limits of how much fat can be added to the breast. Not only are we relying on having sufficient tissue to hold the injected fat volume, but if we try to add more and more, we get to a point where the breast is trying to expand against an unyielding surrounding fascia, with the consequence being that the tissue pressure in the breast increases. Which matters a lot, becuase those little blood vessels that the breast is trying to grow into the injected fat to keep it alive have very low internal pressures, so if the breast tissue pressure increases too much, those little blood vessels get squashed, which means no blood can flow into the fat graft, which means more of the fat dies.

This is precisely why that idea that you'll often hear repeated about "adding twice as much fat as you want to keep" is such an idiotic concept - it is basically a self-fulfilling prophecy of fat necrosis by adding more than you should and increasing the tissue pressure resulting in more fat cells dying. Classic.

Ok, so far then we have the importance of blood supply and oxygen diffusion which requires fat to be injected carefully in wee tiny little ribbons. And we have the importance of not trying to add too much to avoid increasing the tissue pressure in the breast. Both vital concepts.

Now, beyond the injection technique, the surgeon must also consider two other points: how to maximise the number of viable fat cells that are harvested by liposuction, and how to optimise the graft (prior to injection) based on the technique of fat graft processing.

Regarding maximising the number of viable cells, there is a bit of contention in the literature.

My feeling is that we should be using comparatively gentle liposuction techniques with the correct cannulas and low pressure aspiration to avoid rupturing the fat cells and releasing the (strongly pro-inflammatory) oil contents of those cells. That seems logical. So I would argue that techniques like VASER liposuction are not compatible with fat transfer viability. However, I accept that there is literature which claims to show that VASER liposuction can be used with adequate viability of the fat cells, and even some papers that claim superiority of VASER over standard liposuction. Suffice to say I think there is inadequate data to come to any hard conclusions at this stage.

On the other hand, it is quite clear that fat transfer processing makes a difference.

Most surgeons who perform high volume fat transfer would accept that filtration systems are essential to facilitate the gentle washing, drainage and preparation for injection of the fat cells. And yet there are those who do liposuction (with all of the associated fluids and blood and oil mixed in with the fat) and just re-inject that rubbish and wonder why it doesn't work.

The short version is this: we want a clean, relatively "dry" fat for injection. Any associated fluid is just wasted volume being injected into the breast, and any associated blood or oil is pro-inflammatory and will potentially lead to a strong immune response to the injected fat with loss of volume.

So, if it is done properly (right harvest technique, right processing technique, right injection technique), fat transfer works. And once that blood supply has grown into the injected fat, the fat is alive and permanent. It can't go anywhere.

Just remember though that the injected fat will continue to respond (just like any other fat) to body composition changes. If you lose weight post-op, the fat injected into the breast will then shrink - which may given the impression of volume being "lost" - but equally, if you gain weight after surgery, the fat will grow (which may be a bonus!).

The general idea is that you want to have fat transfer done when you are at a stable long-term weight. If your weight is going to move in any direction after fat transfer, you want it to go up a little bit rather than down! Anyone who advises patients to "gain weight to have fat transfer" is just setting you up for disappointment, because once you lose the weight again, the graft volume will decrease. So, no hamburger diets please.

Right, so that then adds careful harvest and careful processing to our list of requirements for successful fat transfer, on top of injection technique and volume limits I discussed above.

Now, the corollary of all that I guess is the explanation for what is going on when people have a fat transfer that ISN'T (or at least gives the impression of not being) permanent. What's that all about then?

Well, with what we said above, there are typically 3 explanations for the amazing, incredible shrinking fat transfer.

The first is that the fat transfer was done in a way that didn't allow the transferred fat to develop a blood supply (ie. the injection was done at high pressure; the ribbons were too thick; and/or too much volume was added resulting in increased tissue pressure).

The second is that the fat was added without being properly processed, meaning it got injected with a bunch of waste fluid, blood etc. which made the breast look GREAT for a couple days before all that fluid got reabsorbed, and (if the fat was injected with significant blood or oil content) the immune system was triggered leading to excessive breakdown and reabsorption due to inflammatory stimuli.

And the third thing is that a patient was told to gain weight for fat transfer, which they compliantly did (and here, we're talking about ladies who maybe way 55kg gaining a few pounds through burgers and ice cream and whatever) who then have their fat transfer, which proceeds to shrink as they revert to their normal body weight. This last one is an illusion of sorts - the fat may well have survived, but if you lose weight, and it shrinks, there may be very little evidence of it being there, especially when only injected in a modest volume.

A final point I would raise is this: there is (for each patient) going to be a critical threshold of injected fat volume, below which any change is just not going to be perceptible. So, if you have a very small breast, and perhaps 100-150cc can be added to your breast volume, then proportionately that may represent a significant change that you will see and appreciate. On the other hand, if you add 100cc to a larger pre-exsiting breast volume, it is likely to kinda disappear in there - the proportional change isn't going to be significant. This is always something you have to consider with fat transfer.

Second: proper fat transfer takes time.

This is where we have to talk about money. Because time is money people, and we all know it.

It is very clear that there are a few characters around the place who will be happily charging perhaps $15-20k as a surgeon's fee for an implant breast augmentation (although more commonly we'll see surgeons charging between $6-8k), on top of which is then added the anaesthetic, hospital and implant costs.

Which is all well and good, but remember that breast augmentation with an implant takes between 45-60 minutes for most surgeons who do it frequently.

That is a hell of an hourly rate.

Fat transfer takes me about 2 hours (sometimes a bit more). Which means I am taking 2-3 times longer to do a fat transfer than it would take another surgeon to do an implant-based breast augmentation.

Why? Well, because my patients looking for fat transfer are slim, we have to be very careful with the lipo, we normally have to to lipo with them lying first on their stomach (what we call "prone" position) before flipping them back over to do the fat injection, we have to process the fat, and then, finally, we have to properly inject it.

So fat transfer takes time.

If you then look at the costs for fat transfer and consider that with respect to time spent, outcome, risks of complications and so on, then you'll be able to do the sums properly to figure out if you think it will be worth it.

If a surgeon is telling you they can do a fat transfer in the same time as they do a breast augmentation with implants, then chances are you'll be getting a dud operation. Simple as that.

Third: you can never separate the surgeon from the outcome of fat transfer.

One of the biggest issues I have with commentary on fat transfer is that it is often provided by people with inadequate training, experience or knowledge. And that matters.

Unlike breast implants, where a half trained "cosmetic doctor" can still, to some extent, expect to achieve a fair result, I don't think the same thing can be said of fat transfer.

There are undoubtedly elements of the procedure which simply require experience to execute correctly and there are technical steps that cannot be ignored.

I think this is why, when patients do experience poor outcomes from fat transfer, it is nearly always attributable to the surgeon performing the procedure - if it is done well, and done correctly, then the procedure works.

Fourth: fat transfer outcomes remain variable (and not always predictable).

Which means you have to understand what you're getting into. The rationalisation for fat transfer I think is that it is natural; or to put it another way, fat transfer is NOT an implant. Consequently, you get natural volume enhancement which IS permanent, without the requirement for future surgery (which is an absolute given with any implant), without the risks (bleeding, infected implants, maybe BII etc.) of breast implants.

What you don't get is the higher predictability of an implant - a fixed shape prosthesis which can force the breast to change shape accordingly.

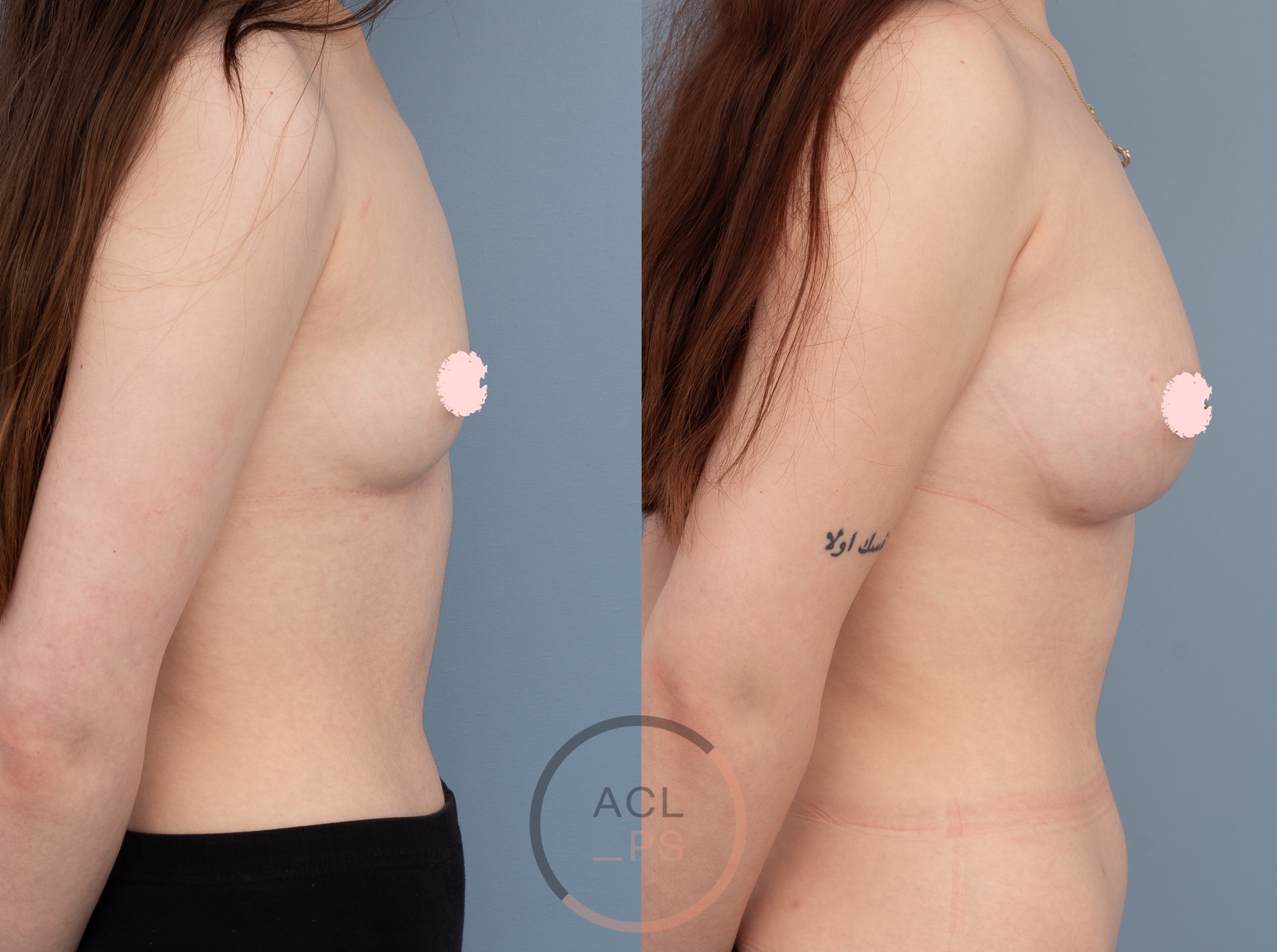

I think the best way to consider the effect of fat transfer is that it will take your current breast shape and make that shape a bit bigger.

If you don't like your breast shape, and you want to change it, then you need to use a different technique (whether that be implants, or a mastopexy).

You also don't get the ability to nominate your degree of enlargement. There is no jumping from an A cup to a D cup with fat transfer.

One cup size enlargement is a fair estimate. Expectations really do matter here.

One final comment for ladies who are explanting (and doing fat transfer at the same time).

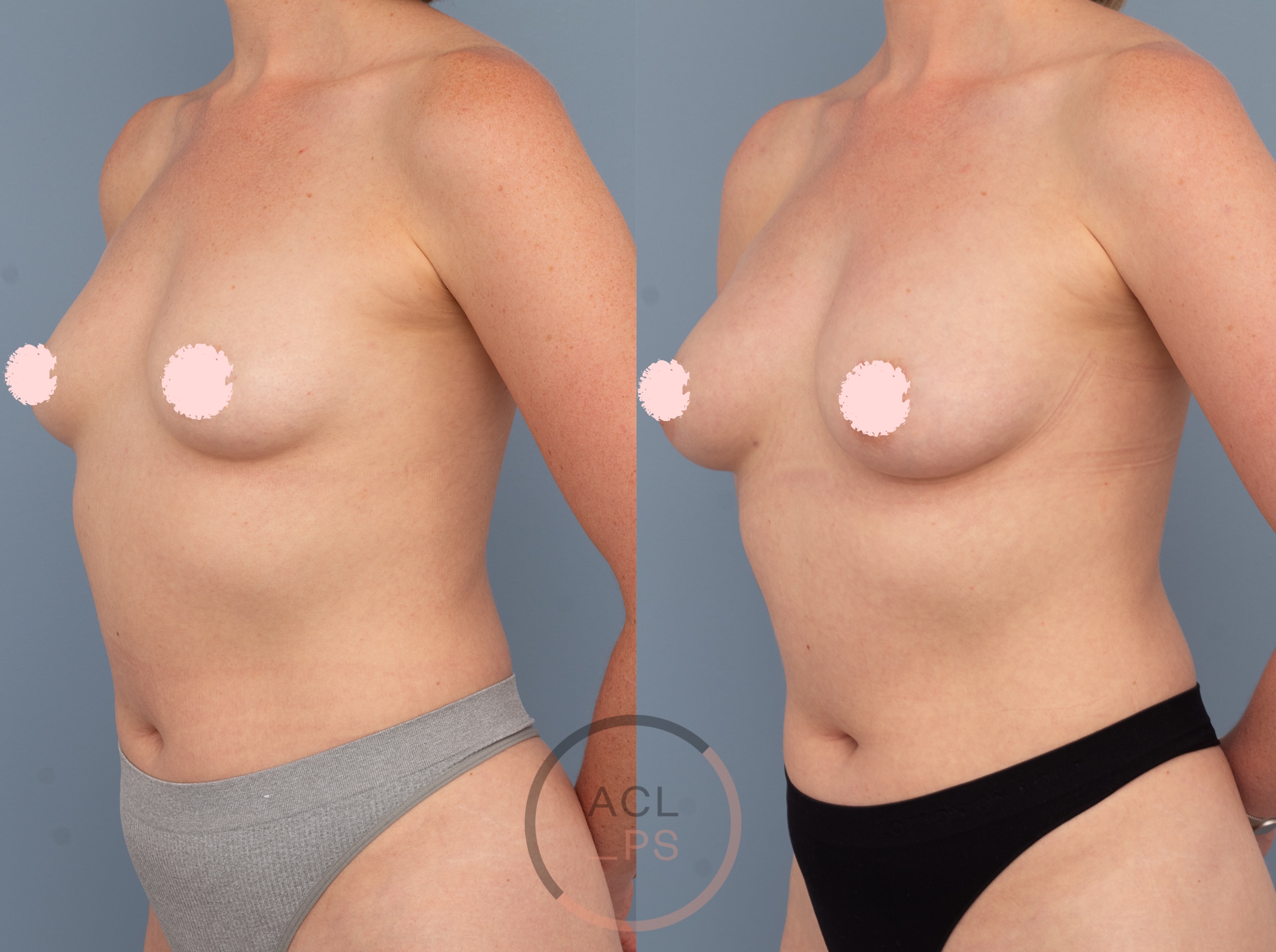

If a small breasted lady has a fat transfer, her before and afters will show a difference. The breast will be a bigger. Sometimes that effect might only be subtle. And to be honest, fat transfer doesn't always photograph that well.

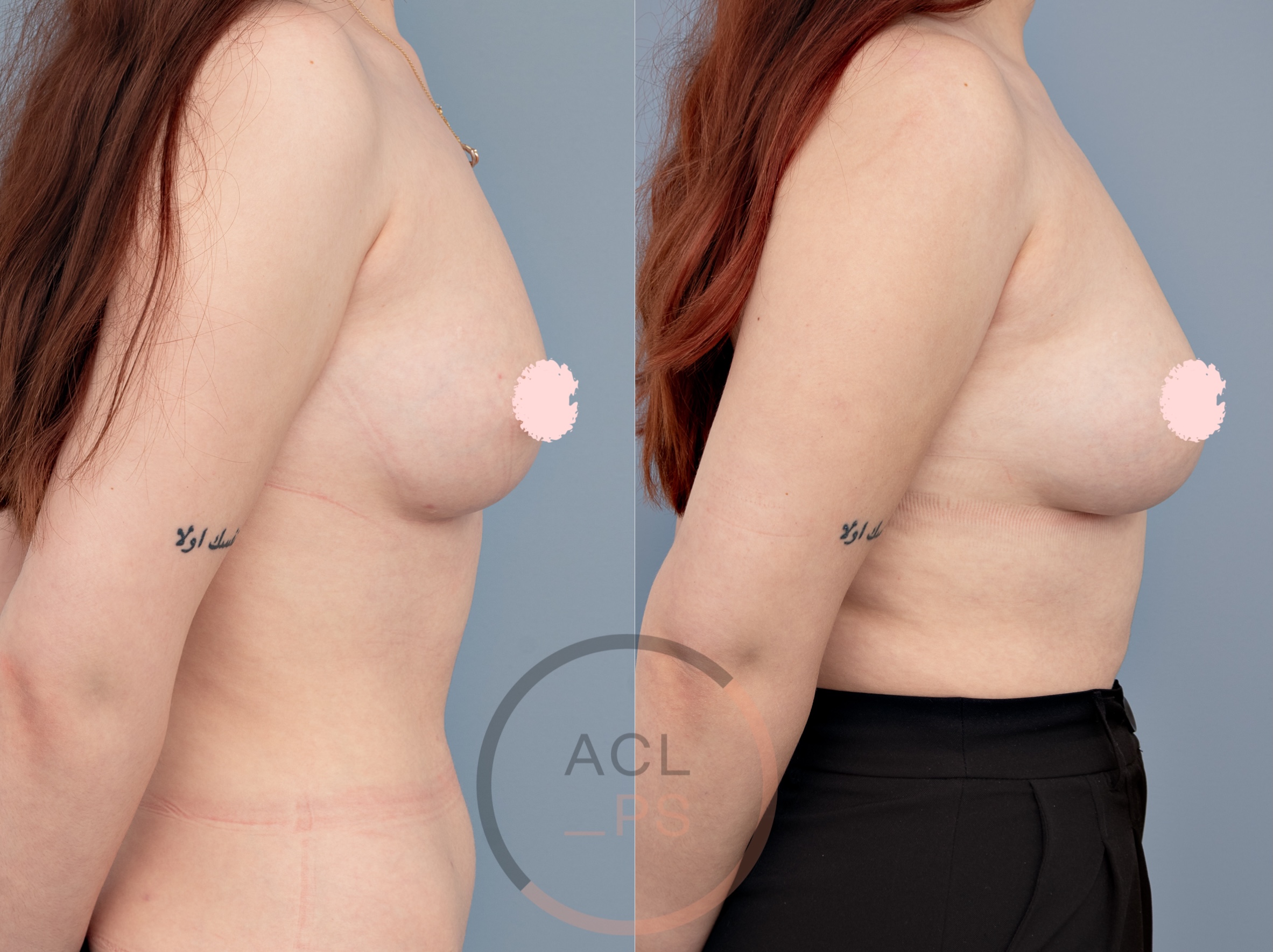

If, on the other hand, you have implants (especially biggish implants) and you have opted to remove them and do a fat transfer at the same time, your before and after photo will always show a significant size reduction. In that context, you can't really see the effect of the fat transfer, and you'll hear me say something like "you're about 1 cup size bigger than you would have been" and you kinda have to take that on faith.

This is a perspective problem.

The alternative for ladies who are explanting is to consider staging their procedures.

Explant first, where we do everything possible to refine the shape of the breast.

Then do fat transfer at a second stage, which allows you to go from a small breast to a larger breast, and more importantly, you have the perspective (and the before and after photos) to allow you to actually see what the fat transfer has done.

Obviously that isn't for everyone, but it is something to think about.

The summary.

Fat transfer does work. It is permanent.

It isn't for everyone.

It can't do what implants do. But that is kinda the point.