"There is no evidence to support this statement".

I recently had another research paper accepted for publication. Interestingly (to me anyway), in the peer-review process, I seemed to encounter a bit of resistance to my work, and I can't help but feel that this has more to do with some of the reviewers' opinions on explant procedures and capsulectomy than it does with concerns about my article. Let me explain.

The whole point of peer-review is to ensure that reviewers are able to objectively consider a research paper and adjudicate on its suitability for publication based on a number of factors: novelty/originality, intellectual rigour, methodology etc. In essence, the reviewers should be determining whether a paper contributes to the body of knowledge that exists in a meaningful way.

Of course, reviewers bring with them bucket-loads of biases, opinions and endless subjectivity, and this is thought to be combatted best by having multiple reviewers to ensure that where disagreement exists among the reviewers, the author receives a range of comments in feedback (good and bad) to progressively edit or modify a paper prior to acceptance.

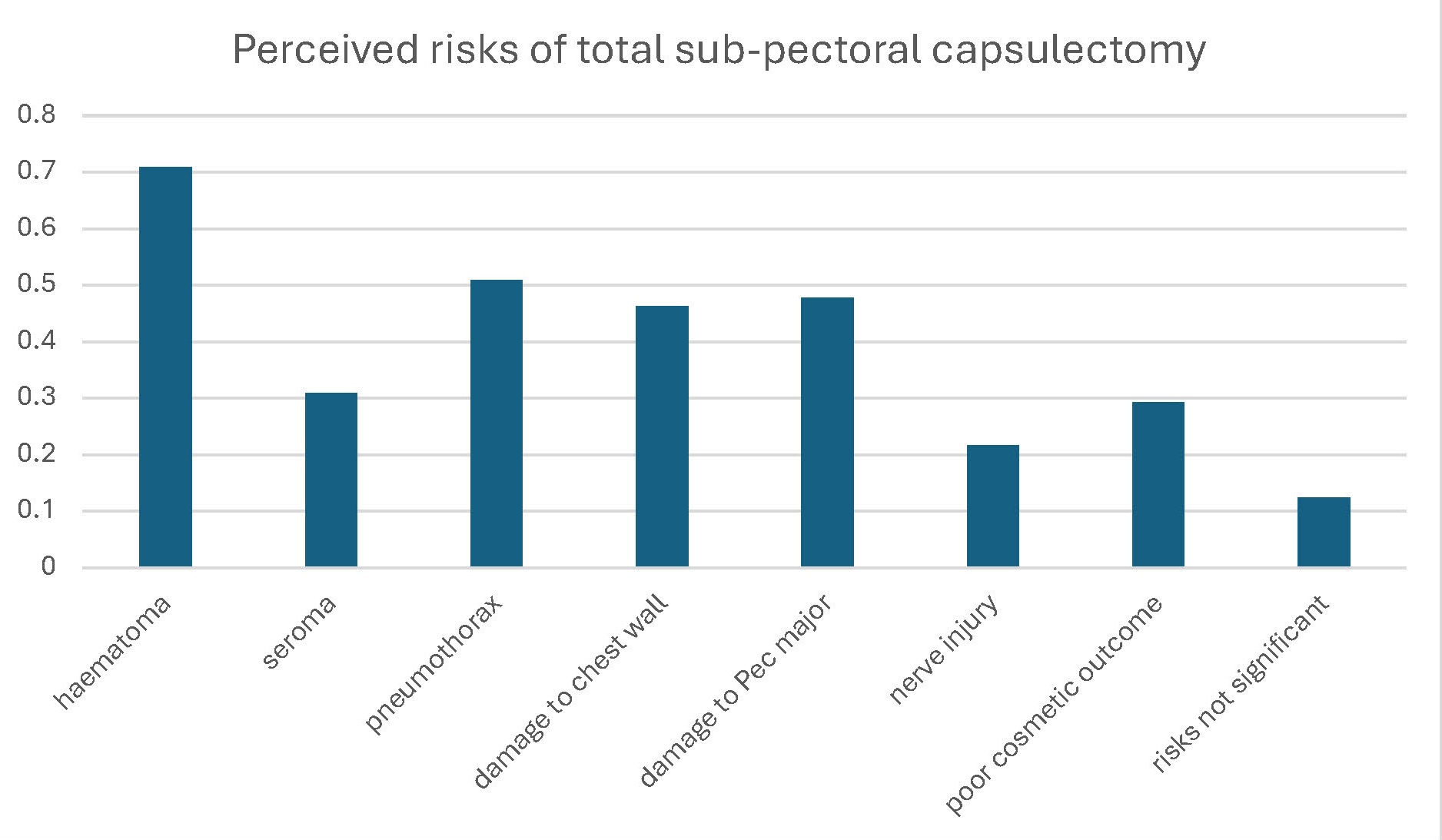

Now, one of the things I find fascinating is when a reviewer takes issue with a submitted paper on what seem to be largely ideological grounds. Let me give you an example. My current paper looks at the ways in which surgeons approach explant procedures in an attempt to understand their pre-existing opinions and whether those opinions are grounded in "evidence", and more importantly whether their practice is being determined by opinions that are not at all supported by evidence.

The fact that "evidence" can only arise from asking questions for which there are no current answers appears to have escaped these reviewers.

In my discussion of this paper I have raised a few conjectures - there are so many unanswered questions relating to explant surgery that it is impossible not to - and several reviewers have tried to take me to task for making comments that are not "supported by evidence". The fact that "evidence" can only arise from asking questions for which there are no current answers appears to have escaped these reviewers.

So we're back to "evidence" - whatever that means - and the ways in which "evidence" can be used to both stagnate and progress our understanding and knowledge.

Evidence-based surgery...and when that is a problem.

I think most people would be familiar with the term "evidence-based medicine". The idea that through repeated experimentation (or in the case of medicine, clinical trials) performed in an ideal way (preferably with randomised selection of patients into groups) with results being assessed by researchers who are blinded to the grouping of patients, we can arrive at an understanding of whether an intervention (be it medication or surgery) "works".

Now, in reality, evidence based medicine is not perfect. But that being said, it remains the most robust way of challenging the status quo by proving that a new intervention is superior to an old intervention.

The problem is that it is far easier to "randomise" a patient to a pill, or an injection, than it is to randomise someone to a surgical operation. When testing a medication, patients might be given a placebo - a sugar pill, a saline injection - rather than a treatment medication. But how do you perform a placebo operation? Obviously you can't.

Now that isn't to say that randomised control trials can't be done in surgery, but it is harder. Rather than compare an operation in one group to not having an operation in another, we instead test a new variant of an operation to the existing standard procedure that is most commonly performed - both groups have an operation, and short of opening people back up again it is often not possible to know which operation was performed.

That being said, what tends to happen in surgery is that we rely on lower level evidence in many cases. And that looks rather different. We might rely on the experience of a single hospital, or a single surgeon, in doing a novel procedure, with analysis of the outcomes. There is a requirement in that case to then see if outcomes are repeatable by other hospitals or surgeons considering their own experience with the same technique. But this lower level evidence is subject to greater risk of bias and misinterpretation, so it requires multiple instances of repetition before it can be concluded with any degree of certainty that a given intervention might be superior to an old one.

Now, unfortunately, even this lower level evidence is absent in Plastic Surgery. Let's take the obvious example - breast augmentation - and consider that for a second. I've previous discussed my concerns with the concept of "dual-plane" as being totally devoid of evidence to support it. So let's consider a few questions.

Firstly, has there ever been a study which attempted to directly compare "dual-plane" breast augmentation versus "on top of the muscle" techniques? No.

Secondly, have there ever been longer term series of cases of dual-plane augmentation to allow comparison to a similar cohort of contemporary over-the-muscle cases? No.

Thirdly, is the evidence for dual-plane augmentation normally supported by comparisons between a contemporary cohort of patients having dual-plane augmentation versus a historical cohort (with many other variable at play) who had previously had over-the-muscle augmentation? You bet.

And lastly, is the so-called evidence for dual-plane augmentation almost universally supported by the manufacturers of breast implants, and in particular, those manufacturers who wanted to push the use of their new "anatomical", tear-drop shaped breast implants in the 90's and early 2000's? Yeah...exactly.

However, let's also be fair to the concept of dual-plant augmentation. Whilst I totally disagree with any surgeon who comfortably concludes that the dual-plane technique is the definitive solution, the ultimate technique as it were, I do consider dual-plane technique to be representative of iterative change. And I think iterative change is sometimes an entirely valid goal. But iterative change is never an end-point. It is simply representative of progress on the march to inevitable improvement. So dual-plane breast augmentation is best viewed through the contemporary lens as a historical step from which we should now be moving forward in many cases.

If we ask the question, "was dual-plane breast augmentation better than the historical forms of over-the-muscle breast augmentation from the 1970s?", then I think we can comfortably answer yes. But that isn't an apples-and-apples comparison (hell, it's hardly even an apples-and-oranges comparison). So, if we then pose the more appropriate question, "is dual-plane breast augmentation better than contemporary over-the-muscle techniques with modern implants?", then the answer is unclear - I would argue the answer is no, but (here's the punch-line) we don't have enough evidence to conclude that modern over-the-muscle breast augmentation is better than dual-plane breast augmentation.

Whilst I totally disagree with any surgeon who comfortably (and often smugly) concludes that the dual-plane technique is the definitive solution, the ultimate technique as it were, I do consider the dual-plane technique to be representative of iterative change.

I would argue that Plastic Surgery demonstrates very little in the way of truly evidence based medicine. There is plenty of opinion, there is a lot of bias, there is an overwhelming commercial driver of many of the decisions Plastic Surgeons make, and a huge amount of the so-called evidence in Plastic Surgery relies on a sort of circular logic that goes like this: 25 years ago some well known American plastic surgeon in a major University Hospital publishes a small series of cases (the fact that the publication was accepted is often due to institutional biases in the publication process of our "peak" journals); there is almost always an "algorithm" presented for decision making; subsequent surgeons publishing their experience reference the original article; the original article becomes heavily cited, and in so doing becomes, ipso facto, "evidence".

Whilst I have argued many times that "experience" is NOT "evidence", that is often how it works in Plastic Surgery.

The status quo...or how not to rock the boat.

We intermittently will see upheavals in plastic surgery, and there can be these halting steps forward, but there is definitely a sense that surgeons prefer the security of the status quo, because that provides a commercial legacy that is reliable.

Let me offer an example.

Breast augmentation has been performed by plastic surgeons for 50 years.

There has been some attempt in the last 25 years to generate "evidence" of the "safety" of certain approaches. We can think of this as it relates to implant technology, and surgical technique.

Let's consider implant technology first. As I've explained elsewhere, implants have evolved over the last 50 years (of course) but with each evolution, the problem for which a solution was sought was rarely the consequence of a single implant-based variable. But don't mind that. So through the various eras of implant-based breast surgery, we've seen smooth surfaces change to textured surfaces; silicone fill changed consistency, then changed to saline, then changed back to silicone; we've see materials science evolve to allow better understanding of the interaction between biology and prosthesis. And with each era, we've seen progressively better attempts to apply modern concepts of data gathering and critical analysis. Which is great. But is that data always looking at the right thing?

So, the "evidence" that is most commonly considered with respect to implant technology comes from (mostly) manufacturers, who are obligated by the FDA (in the USA) to prospectively capture data for a cohort of patients (note, there is no comparison group here except for the historical). Now these long-term studies typically form the basis for other health jurisdictions around the world when considering whether to approve implants for use, whether that be here in Australia, in Europe, or elsewhere.

The FDA studies have been a feature now for over 20 years (since the end of the "silicone moratorium" in America). But what are those studies looking at? Well, generally they're looking at a few hard end-points. For example, these "core" studies consider events like implant rupture rates, re-operation rates, and capsular contracture. None of those outcomes however truly represent the durability of the aesthetic result. Typically these studies are highly selective, which is to say that they carefully select patients who are "less likely" to experience complications. And these studies overwhelmingly include patients having dual-plane augmentation.

And what about surgical technique? Well, this is less helpful. Because in the last 25 years, dual-plane augmentation has been overwhelmingly, unquestioningly accepted as the gold-standard. Admittedly, that may be finally changing, with a resurgence in the use of over-the-muscle techniques in the last 3-5 years, especially in the USA (Australian is predictably slow to adapt). But what effort was made to generate evidence for dual-plane? Well, as I mentioned above, we can summarise this as "bugger all". Disingenuous historical comparisons aside, there really hasn't been much effort to validate the dual-plane approach, but as I've discussed elsewhere, the dual-plane approach was really more about justifying the use of anatomical shaped implants, but the implant companies realised that they needed a better sales pitch, so instead they sold the concept on the premise of reducing capsular contracture risk.

Other aspects of technique have evolved, albeit with rather sketchy support. Broadly we can consider this in terms of reducing the risk of capsular contracture (so-called "bacterial mitigation strategies") and reducing the risk of recurrence of capsular contracture (different concept, and this has more to do with concepts of "plane-change" or, for the Americans, the use of scaffolds and ADMs).

Reducing capsular contracture risk has followed the recognition that capsular contracture appears to largely relate to the inflammatory stimulus which arises from the presence of bacteria in the implant pocket. Not "infection-causing" bacteria per se, but the bacteria that normally and safely live on the skin or in the breast tissue. I'd call that a win for "evidence" in many respects, and one of the few areas where we can say that.

However, reducing the risk of recurrent capsular contracture has suffered many of the idealogical constraints we've seen elsewhere, with a stubborn refusal to accept that the ingredients for recurrence exist within the capsule! So if a contracture is present, no matter what else you do (I'm looking at you USA, with your whole "just make a few slits in the capsule and shove a piece of ADM in there") the contracture will recur if you don't address that. Now, my personal opinion here is that minimising recurrence risk requires a) TOTAL capsulectomy and just as importantly b) a plane change to over-the-muscle, but that still hits up against a hell of a lot of resistance (largely relating to the attachment surgeons have to the dual-plane).

Ok, so while there are some overall improvements in what surgeons do based on what looks like actual evidence, what we can see is that over the last 25 years, the changes in practice are...minimal. And the main reason for that? The surgeons themselves. Like I said above, the status quo is comfortable.

"There is no evidence to support this statement".

Which brings me back to what I wanted to talk about at the start.

There is a very long history of Plastic Surgeons being all too willing to overlook deficiencies in the evidence for certain interventions. Which makes it especially interesting to see "evidence" then being used to potentially block new or contentious ideas which challenge the status quo.

This, to me, is clearly a case of double-standards.

The fact that I choose to focus my work, and my research - to be fair, I don't see myself as being especially academic, and I don't pretend that my "research" is ground-breaking, but when there really isn't much other work being done to look at explant surgery, something is perhaps better than nothing - on explant surgery seems to represent a problem for some of my colleagues. Maybe they view the ideas of capsulectomy and/or explant surgery as being threats to the established order of breast augmentation. Maybe they worry that, as breast augmentation decreases in popularity whilst explant is surging world-wide, their comfortable, lucrative practice will be forced to evolve in a direction that feels challenging to them.

But when "evidence" is wielded as a tool with which to demand that some new(ish) ideas are suppressed, I think we might have a bit of a problem.